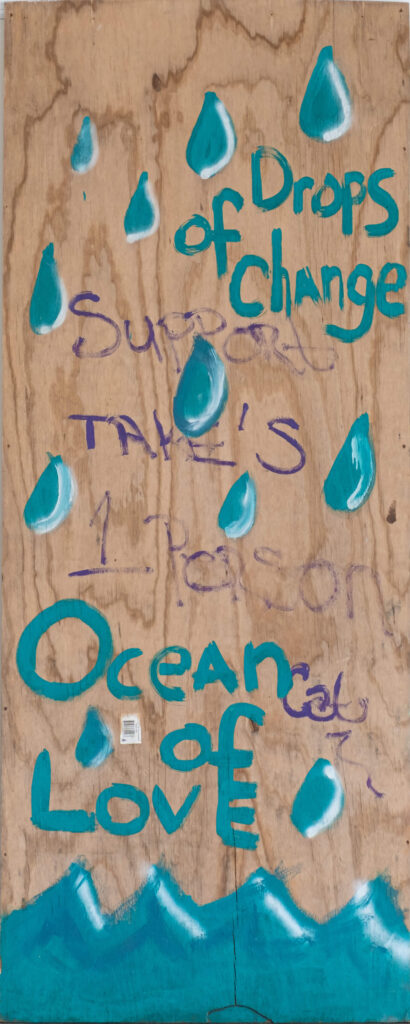

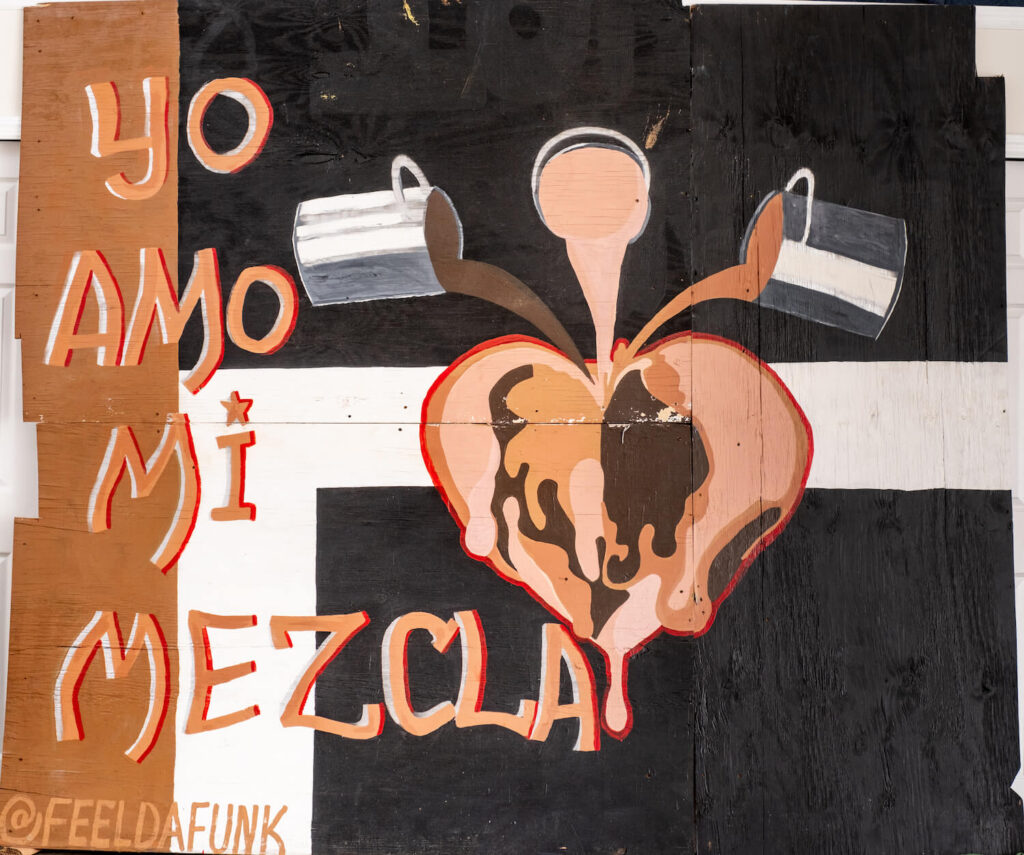

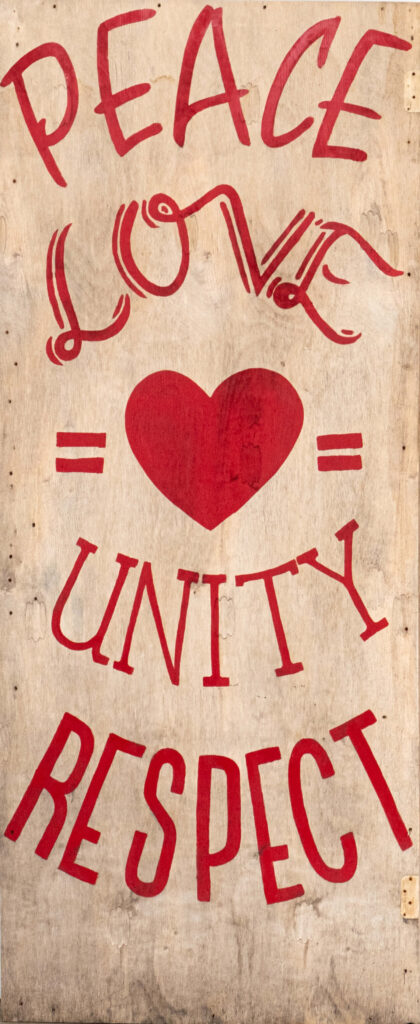

In the wake of the tragic death of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, and the ongoing challenges posed by the pandemic, the Inwood/Washington Heights neighborhood witnessed demonstrations advocating for an end to racial violence. In a heartening display of solidarity and community spirit, store owners themselves invited a group of artists to paint their business fronts. What initially began with just one or two artists quickly gained momentum, as approximately 15 individuals joined forces, creating vibrant artworks that encompassed a wide range of themes, from expressions of solidarity, Latino identity, the Black Lives Matter movement, and Dyckman/Washington Heights.

As the artists’ efforts gained momentum along a significant portion of the stores in the lower Dyckman area, they became known as the Collective of Dyckman Muralists. The collective embarked on a mission to paint as many stores as possible, with store owners themselves generously contributing to the procurement of paint supplies. The process fostered a sense of unity and togetherness within the community. The resulting murals, showcasing the artistic talents and the resilience of the community, found a temporary home on display at the Riverside Inwood Neighborhood Garden (RING) for several months. However, the park authorities eventually made the decision to remove them.

In response, the Northern Manhattan Arts Alliance (NoMAA) has taken up the mission of preserving these impactful murals in the digital space. Through this endeavor, NoMAA aims to provide an enduring testament to the unwavering strength and creativity of our community, ensuring that their powerful message continues to inspire and resonate with audiences far and wide.

The 2020 Collective of Dyckman Muralists: Street Art and The Power of Unity

Interview with Daniel Bonilla a.k.a @artmandan

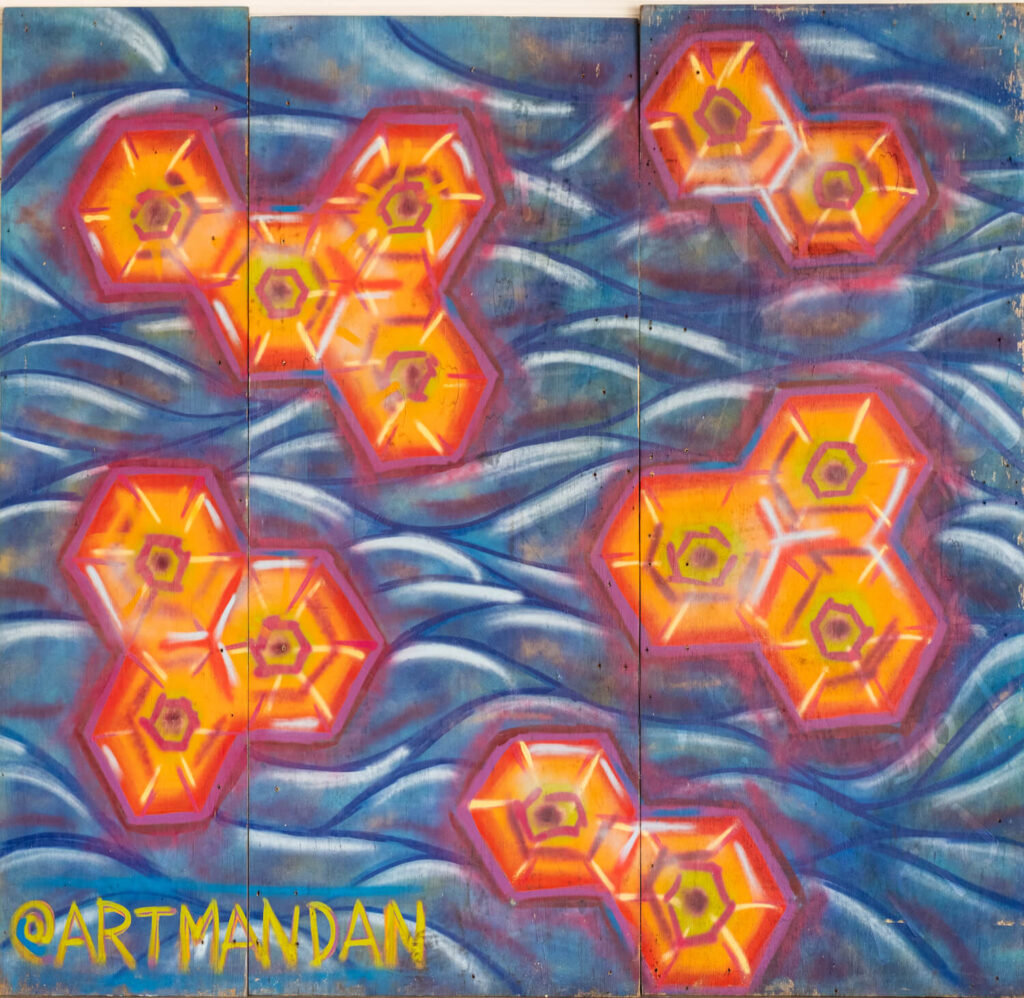

Daniel Bonilla, better known by his captivating street art pseudonym @artmandan, is a creative force who has been igniting New York City’s urban landscapes with his artistic vision. With a spray can or paintbrush in hand and an audacious imagination, Bonilla seamlessly blends graffiti and fine art, transcending the conventional boundaries of artistic expression.

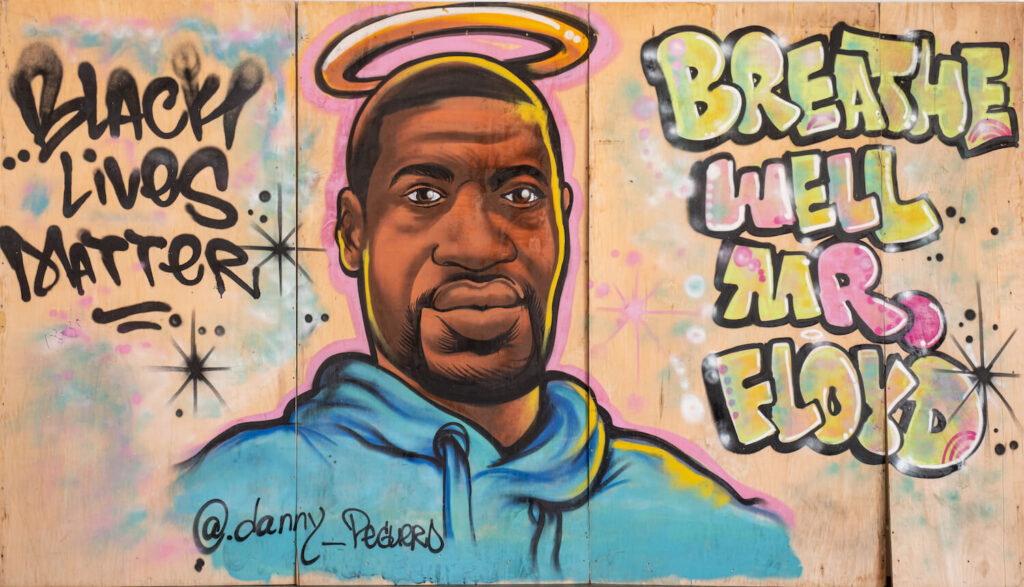

In the summer of 2020, Bonilla joined forces with a group of like-minded artists hailing from the Inwood-Washington Heights area. Together, they embarked on a mission to artistically convey the historic significance of the Black Lives Matter movement through a series of vibrant and thought-provoking murals. Over time, Bonilla emerged as a prominent figure within the collective, now known as the “Collective of Dyckman Muralists,” as he strived to preserve the profound social and cultural resonance of the murals they created.

In this conversation, Bonilla reflects back on the collaborative journey that captured the essence of that transformative summer amidst the pandemic, and on the importance of safeguarding the memories narrated through their artwork, which continue to resonate with profound social and cultural themes.

Q: How did your journey into painting begin, and what does the act of creating art mean to you?

DB: I’ve been involved with art ever since I was like four years old. I’ve always tried to stay in the art community, in the art field, but it wasn’t until 2017 when I started trying to make my career more solid as an artist. I told myself I was only going to take jobs that dealt with painting. I started painting commercial buildings. From there, I went to work at a company called Colossal Media where I painted my first murals. I always was rooted in art, and I just didn’t know how I was going to do it.

Q: How did you become part of the Collective of Dyckman Muralists? How do you remember the summer of 2020 in Inwood-Washington Heights?

DB: George Floyd died on May 25, 2020. After his death, a lot of demonstrations started happening because people were angry. It was a city-wide thing where business owners were boarding up storefronts because they were afraid of being rioted or looted.

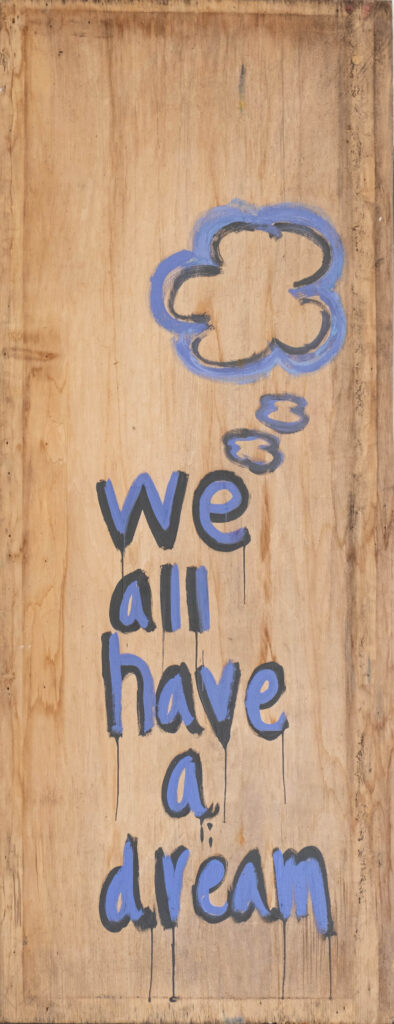

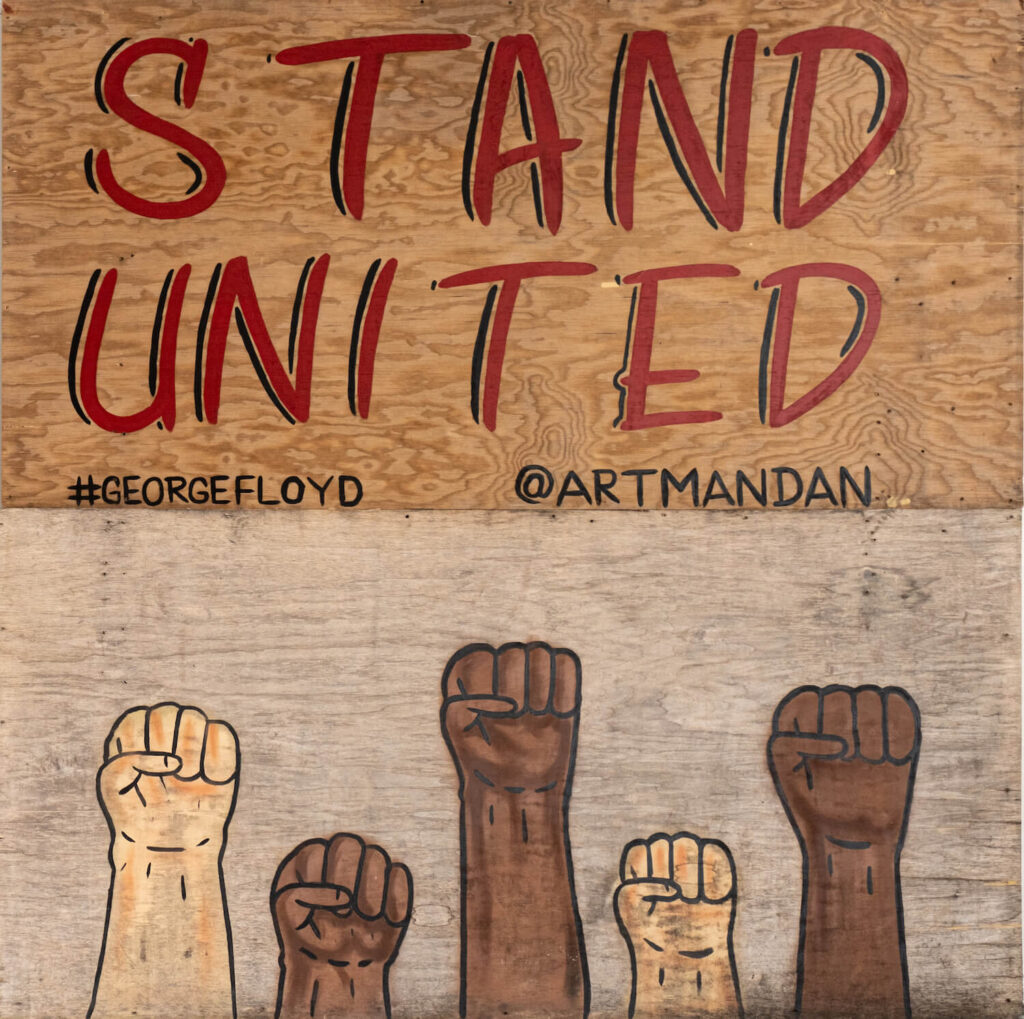

I was walking down the block when I saw people painting on these boards. I asked who was the person in charge who I could talk to so I could paint. Everyone was pointing at one person or another. I didn’t know who to speak to. A friend of mine who was painting right there, told me they’re letting us paint over here. I was like, Oh, my God! This is like a perfect chance for me to express my soul. I did this super simple “Stand United” mural with the hands going up, representing the power of unity.

Q: How was the project an avenue for creating communities?

DB: I understand the importance of community, and the person who let us paint these boards also saw the value of community. It was something that I haven’t experienced since college, where you have a bunch of like-minded people sitting in the same room, learning something new, everyone sharing their ideas with each other. So I found this super exciting, it was an opportunity given to me. I then ended up going with it and trying to keep everyone together.

I love painting in the Inwood-Washington Heights area because it resonates more with people. I became part of the Dyckman Mural Collective in 2020, it was a group of about 15 artists who just wanted to paint. During that time I was just doing very free-handed things from the heart. Nothing was really planned. The collective started very organically. I was like one of the front runners because I was more into the art than most of my other friends. I was more into wanting to keep us in the loop and somewhat united.

Susana, the owner of the “Mama Sushi” restaurant gave artists from the area the opportunity to paint there. One person was out there painting with extra paint, and then my friend called me, he said, “come over here because the owner from Mom’s is letting us paint.” I said, you know what, I’m just gonna go and have fun. That’s how I was able to paint her storefront. She saw how eager we were to paint everything. From there it was like a trickling effect. She then called the other business owners in the area. We were there for the opportunity.

Susana was super wonderful to give us that chance to express ourselves and be part of something cool. She understands people relations and gives people opportunities. That’s why she has a very successful business. She was able to give us opportunities and to have us paint to also elevate her restaurant, and in that way her involvement with the community.

Q: How long were you guys painting during that period?

DB: In a span of two weeks we painted that whole block. Now, looking back, I was fortunate enough to not have a job at that moment, to be able to have that free time to go out and do these things. We weren’t getting paid for any of this work, other than through recognition. I’m never a fan when people insist on getting paid when they’re not at a level where they can be asking for the price that they want. When you have a gift, and you can give it to people, go for it even if you’re not getting paid, because it might impact someone in the future in a positive way. I remember I got recognized in my neighborhood. That brings me so much joy. Just keep on doing the work, keep on connecting with people, being part of that community, helping other people out as much as possible.

Q: What was the community’s response? How did they engage with the murals you guys created?

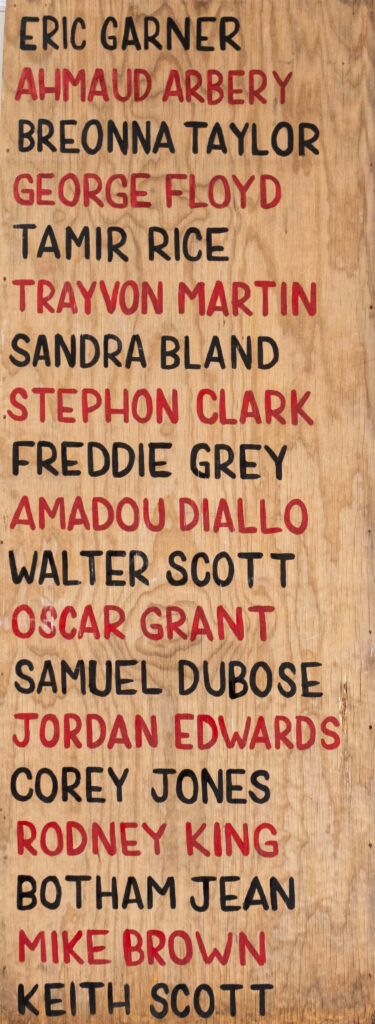

DB: The day I started painting these mural people were walking by and looking up all the names. They all have something in common, they were all victims of police brutality. It was very powerful because sometimes people would come in and ask me “who is that,” or would give me more names I didn’t know.

After a month, some business owners decided to take down the murals. It’d have been cool if we were able to bring the murals from one side of the street to the other, where there’s a little park across the street. Some of the murals were destroyed. We were able to move them across the street, but under the condition that we took care of them. I took care of them for about 4 months.

Q: How did you become involved with NoMAA?

DB: My relationship with NoMAA began when I was painting the murals and Martin Collins happened to be walking down the block. He introduced himself and we just kept in touch. NoMAA has been very supportive. They featured me as an artist on their programming. Every Thursday night they showcase artists from the neighborhood, and I was one of the artists that they showcased once. They gave me an award for being part of the Dyckman Collective. I appreciate NoMAA for all the work that they’ve done.

They reached out to Gale Brewer, the Borough President at that time, to try to find the place to store the murals. But we weren’t able to find a place for them unfortunately. We weren’t famous or anything like that, but it was a contribution that we gave from our heart to the neighborhood. We really did work hard to figure out what to do with them. At least we were able to get pictures and to document them. Now we have them in a digital space so more people can see them.

Q: What happened with the Collective and its individual members?

DB: The collective was not supposed to last forever. The Beatles, they only played music for 10 years. For us it was like we were a part of something for that time. Now everyone is doing their own thing. Jesús Santana is working now with NoMAA. Henry Domínguez is working with the Dominican Film Festival. But the collective did help us make more connections with other people and organizations. I’m also doing art on my own terms, moving forward with what happened during that time.